Nurse Log and The IRB Network Altar, 2024

Nurse Log and The IRB Network Altar

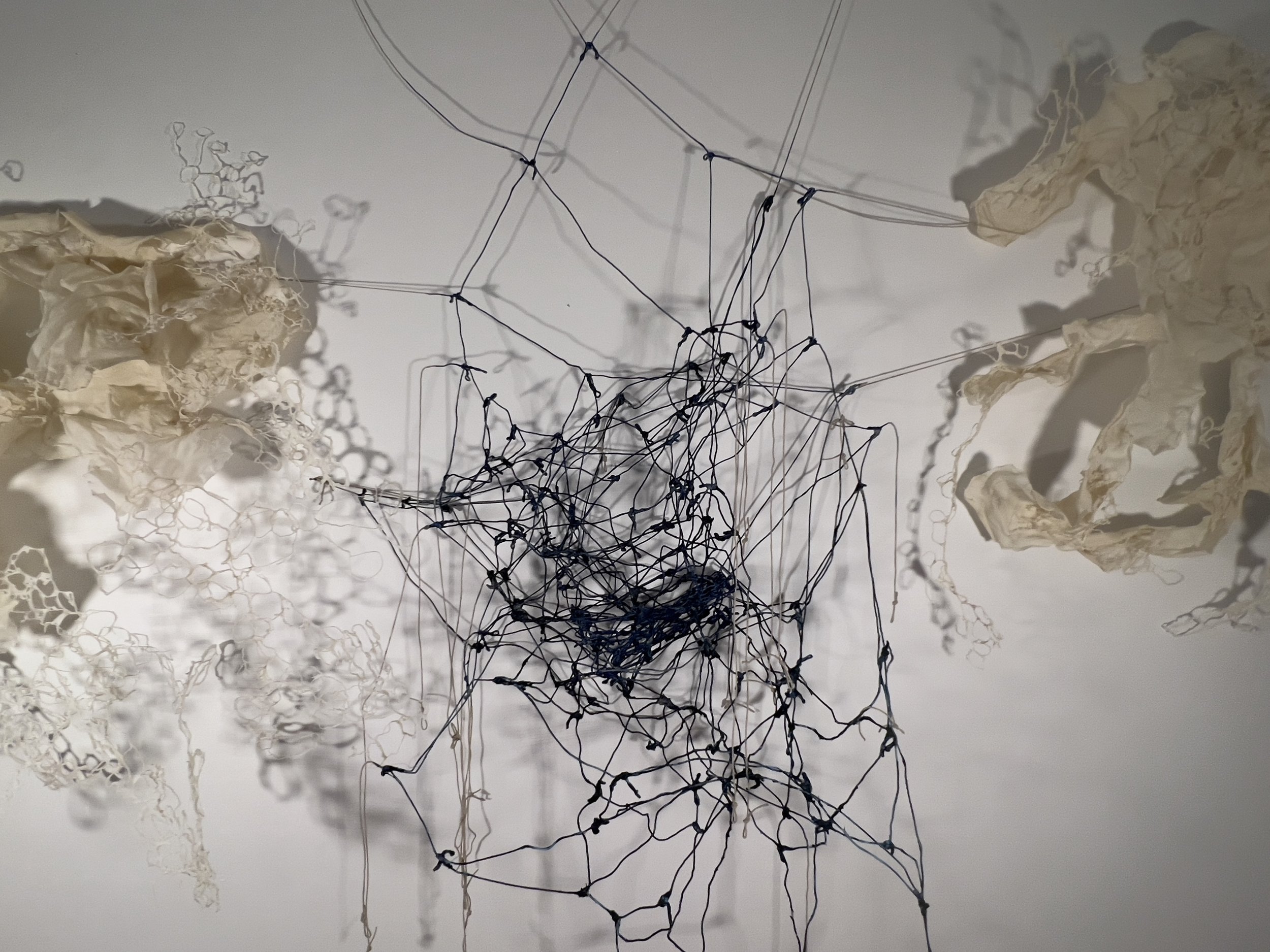

While applying for a University of Maine approved IRB, (International Review Board) to create a field guide, I was also working in the studio- sense making. To understand the process I was pulling together desperate lines, which at first resembled a tornado, four feet wide. As the IRB process altered my intentions, the core of the shape contorted.

Meshing their expectations, and my desire to create a publication for artists, by artists in first person, to give publicity and value to our process - the work kept building. Layered in Beam Paints and University of Maine Softwood cellulose nanofiber (CNF) the shape was formed and coated. The color would change as CNF dried. The excitement of a draft submitted would then be mollified, as I struggled to fit the institution's expectations. I returned repeatedly to make the eye and mind appease, layering my thoughts to counter what the material or committee was responding with.

Sure, the cliche of a net is known, and yet pulling details and coating them with strokes of color and strength kept an archive of response..

Presented here, the net is inverted. The project hung as an example of experience. Paired with the truth of the matter, the nurse log of technology and death. The nurse log is a tree that has been cut or fallen down, leaving a stump and roots to keep the underground networks intact. While many think the dead are done, their life keeps giving, and to that, there is more life in a carcass.

Life Cycle is a recurring theme, much nutrients comes from death. The IRB was approved, the survey was sent out both publicly through social media and pointedly towards artists that I thought might partake. Many artists responded, and many artists started to respond. However, the forms and structures confused, or alienated artists. Certainly the project is not dead, it is the life given to keep going. The field guide is still growing, and seeks more first person narratives. However, perhaps not through the Institution's rectangles and squares.

Eclipse 2 & 1, and the IRB Network

Eclipse, and The IRB Network.

Eclipse 2 & 1, University of Maine Cellulose Nanofiber ( CNF)

Prior to installing the work, these were hung in my studio. The two side works are together in a secret window at the Lord Gallery for the summer of 2024.

First, a great deal of my art practice is about creating a library of ideas that can be reformed together, like stories and sentences.

Second, every thing is co-evolving, these came from the Aceae work. The extension of what the work is, is extended beyond by shadow. The experience of the viewer as a sense maker is relevant to its success. It is the materials response, and perhaps my hand, that lays the map of movement. The eclipse is not just the light to darkness, the sun and the moon, the silence of birds and foxes, the engagement of ceremony or disregard of its happening, it is all of it. All at once.

Technology, & Workshops

Andragogy, Technology, and Co-Evolution

Here is the context for the sense making flying vessels. This winter, teaching a Cellulose NanoFiber (CNF) community workshop at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, I encouraged students to bring things from their own practice to facilitate their own research. Amongst other items, Ceramist Lila Balch brought a small bit of copper netted tubing, that her husband had to block mice from entering the house. The workshop had been designed to hold space for the participants to research, share their immediate assumptions, and then findings. The class happened over two weekends, allowing for the drying time, for collective sharing and multiple intentions to be learned from. This model is used to encourage participants' ability to jump the fence of rules. Can you do this, is a question that is repeated in these instances, and my answer is - I don't know, can you? It is rare to be able to learn about a material in real time, while also experiencing how to extend that knowledge, by giving the self permission to challenge precious art making. Most studio education comes with rules, and it is rare to create those rules one self. An andragogy designed class supports each person to engage, and to share.

Simultaneously, I had been working to design a 3-D knit vessel in hemp, working to pull in technology, as a paradox to my hand work. The vessel was to grow up multiple feet in diameter, from the floor to the ceiling 10 feet high, then branch out and slender down in multiple directions, another 10 plus feet. The vessel was to be a distraction.The vessel was to create a barrier that the viewer had to choose to cross in the thesis show.

Referencing the placarding paintings from 2022, the structure was to represent the edge of the forest, the front wall of the unknown. I had been looking at fiber artists, and while I do not think of myself as a fiber artist, I wanted to collaborate to do so. The design process moved from a loose drawing into a digital diagram for designer Isabell Camarra, at the Composite Center at the University of Maine. The proposition was to test out their machines. The sculpture asked the designer to rethink how to use the machine, to create shapes and possibilities that had not been thought of yet. This in turn would give new skills to create for the composite centers paying clients.

The sense making for collaboration through technology relied on trusting the ability to plan for my imagination. All of it needed to be translated through a woman who had the expertise to implement the drawing into a tangible file and then produce the machine made knitting. My biggest concern was the pivots that naturally occur when making corrections in the studio for visual or structural issues. This process would bring with it several unplanned problems, that I would have to accommodate for in the installation, without the practice in the studio. This, as a sense maker, removed the constant back tracking and problem solving that occurs when making. A bridge is built in multiple directions when making, the ground forward is tested as it is rarely a straight line. What actually happened is the twine chosen to make the work was too heavy, the machine broke repeatedly, and there was never a structure to contend with.

Enter copper into the material list. Copper has worked its way alongside my art practice since I was in college. Its conductivity and ability to carry warmth, shape, form, and be etched has taken many shapes, often to be held, sometimes to cast shadows. These nets were strung out through my studio and laden with very wet CNF, each time I returned to them, after days of drying, images of tree branching reflected back at me, although not in health, rather in decay. Netting would hold material in clusters, forming skin in internal layers. As the shapes developed, they reminded of my chosen mothers, Lynda Benglis and her wire and abaca drawing series. Abaca creates a singular taught dried skin, that pulls on the chicken wire, Benglis would paint these with a colorant with sparkles. The copper now embedded with layers of CNF, held pre-form rings, stacked up the form’s sides.

I was thinking about the armature the netting provided, manufactured to block mice, the material is light and malleable to stuff in holes. The copper came rolled up, and offered what felt like endless length. Knowing the CNF would pull the forms in towards itself stiffening, the areas uncoated remained loose and flexible. The coating brought out a look of white peeled bone or bark, not the vessel of knitted hemp that I imagined, but it started to hold enough form to embed into a structure of knots that would hold the edge of the installation.

Between either hemp or the copper, the new technology came from very old systems. Evolving the way the netting was created did not change the knitting as much as it altered the labor and reliance of know how. Historically as a common process passed down as an embodied knowledge, intergenerationally, our communally, collectively, or even through the internet how to. The hand process can’t help but change the stress of a loop, drop of a stitch, or complicate its output with human error and love. Does the manufactured netting make a product that is comparable, it certainly can drop a stitch.

Is this an example of coevolution of technology?

The harvesting of copper, implications to the environment, humans in its aftermath, and machine parts complicate a long held history. Quite the opposite to the general message of compostable and impermanent materials, however these are not exclusive to their origin. It brings to light that there is nothing used in the show that is not harvested, manufactured, macerated, manipulated by humans for ease, and shipped far from its origin source. If we are to be honest about this, even with the materials considered, they are all through the sieve of society to meet production and capitalism’s demands. Choosing to use them as art materials that can (mostly) be returned to the earth, is a co-evolution of need and use.

All the materials included are products of manufactured technology. By bringing the copper to the forefront of the work, it is an acknowledgement and reframes the work, bringing the paradox to light that this is known. Handiwork places my participation as sense making, after the work of capitalism has already been done.